Design More; Consume Less

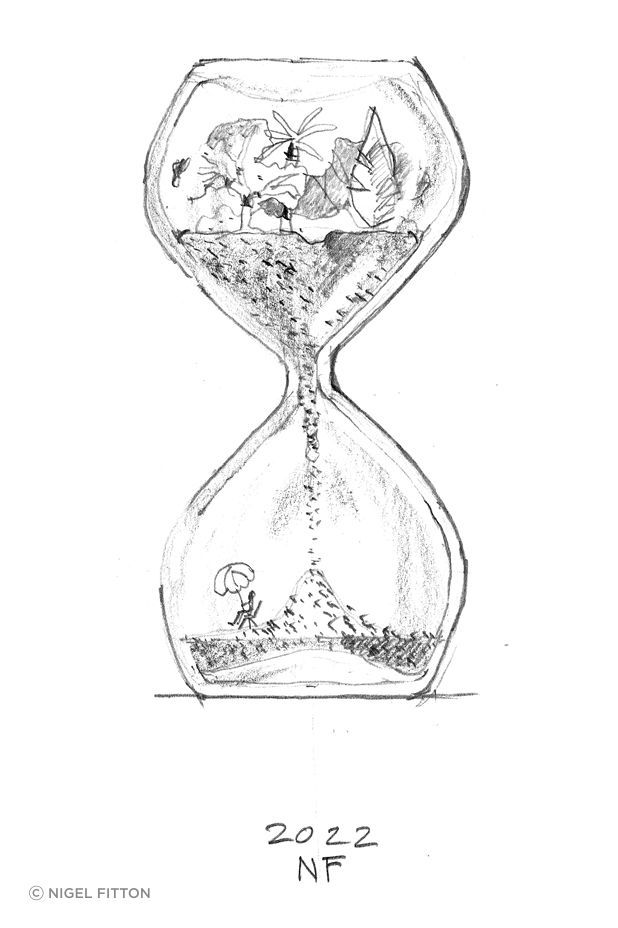

As the issue of climate change becomes increasingly pressing, it is crucial that we understand the connections between design, sustainability, and consumption.

This essay is an opinion piece that explains Antony’s personal views on sustainability and design. This essay is also the premise for a new 2023 podcast series (and potentially a book) where Antony will interview leading practitioners in design areas to discuss the relationship between design and sustainability.

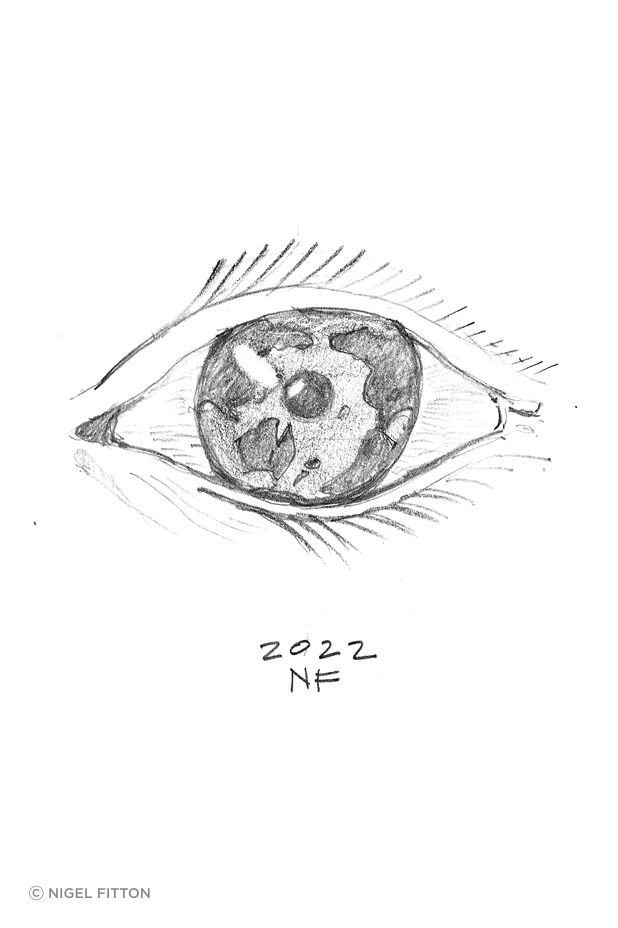

As I visited Shanghai years ago, I was struck by the heavy smog that covered the city. The thick, milky layer seemed to obscure the beauty of the city, once known for its architecture and expansive waterways. While the locals seemed unfazed, I found the smog’s claustrophobic presence depressing and confusing. It made me realize the negative consequences of industrial and technological progress – the loss of contact with the sky and the rarity of seeing stars at night. This loss makes me wonder if we are too clever for our own good, and what we sacrifice in the name of progress.

My visit to Shanghai also reminded me of my childhood, when I spent a summer’s night in Mildura looking up at the twinkling stars filling the sky. During the day, the expanse of the sky was a constant reminder of the vastness of my surroundings. I naively assumed that all children had this experience, but my time in Shanghai showed me that this is not the case. How have we allowed progress and modernity to take us so far away from nature that we can no longer see the sky?

Even if the contact with nature is at a subliminal level, it is essential for our well-being and sense of self. We are not just lab rats in an economic experiment, defined solely by our labor and consumption. By creating environments where natural light is suppressed, we are disconnecting ourselves from what has helped us evolve over millennia. The erosion of our connection to nature occurs gradually, at an imperceptible rate, making it difficult to notice what we have lost in the process. We have moved from the simple rhythms of night and day, and the changing seasons, to a 24/7, always-on, thermostat-controlled existence. We have narrowed our experiences to such a degree that living in a big, urban metropolis is now considered completely normal.

I worry that our desire to control every aspect of our lives diminishes our ability to see beyond the immediate – be it a device, billboard, or computer screen. The decline of traditional media, local community, and the dominance of social media and technology, exacerbate the shrinking of our real-life experiences. This can lead us to believe that we are in control and masters of our destiny, even as the frequent and intense natural disasters, such as bushfires, floods, and storms, remind us that this is not the case.

American astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson argues that seeing stars at night helps reset our ego by reminding us of the vastness of space and the smallness of our planet, and indeed, our own existence. This realisation can be liberating, as it allows us to appreciate the wonders of life on Earth. However, when we lose our direct connection to nature and the environment, we also lose those innate connections to things larger than ourselves. From a satellite’s perspective, it’s easy to question whether we are as intelligent and advanced as we believe ourselves to be, given the destruction we have inflicted on the planet.

It is clear that progress and development do not have to come at the expense of our connection to nature. It is possible to balance the desire for progress with the need to preserve and protect the natural world. It is also important to recognise the value of all types of experiences and perspectives, whether urban or rural. We can maintain a connection to nature even while living in cities, through activities such as visiting parks and green spaces, participating in environmental conservation efforts, and supporting sustainable practices. Ultimately, it is crucial to find a balance between progress and preserving our connection to the natural world.

As designers and architects, we have the power to shape the built environment and the objects within it. However, the pursuit of “iconic” and “award-winning” designs can often lead to unsustainable and exclusive outcomes. The focus on aesthetics and trends can contribute to the problem of unsustainability, rather than solving it. Instead of promoting greenwashing or superficial fixes, design should strive to create desirable and attainable solutions that address long-term challenges such as sustainability and inclusivity.

Design is a multifaceted field that involves solving problems through creative and strategic thinking. In the contemporary world, designers are often called upon to address complex issues such as sustainability and social justice.

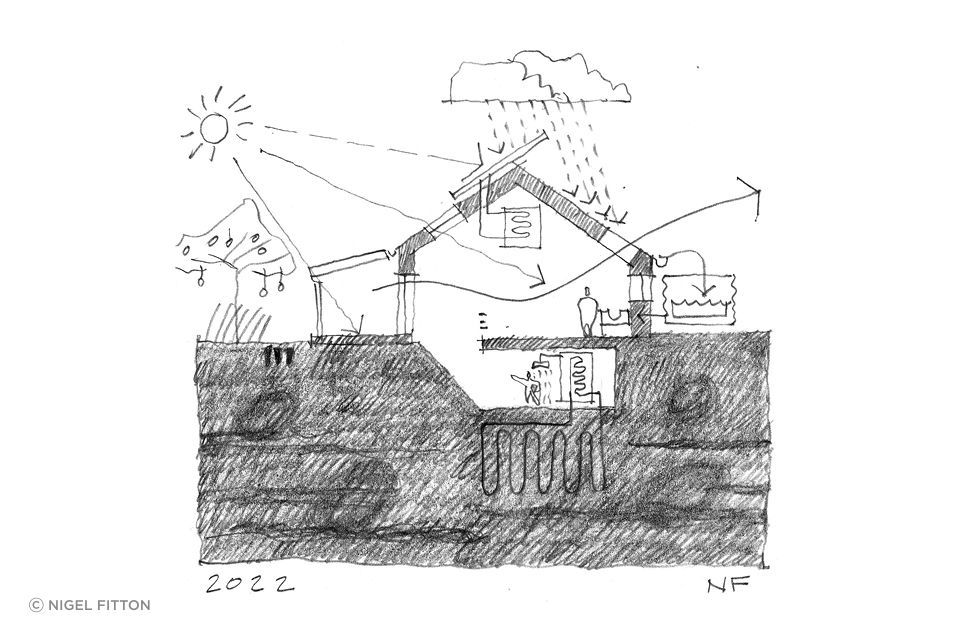

This requires a holistic approach that considers the full lifecycle of a product or environment and its impact on people and the planet. To be effective, designers must go beyond surface-level aesthetics and consider the broader systems and structures at play. This may involve collaborating with other professionals, such as engineers, scientists, and policy makers, to create truly sustainable and inclusive solutions. The role of design is to use innovative problem-solving to create positive change in the world.

As an architect, I have struggled to reconcile my work with the environmental impact of the construction industry. While designing eco-friendly buildings is important, I cannot ignore the fact that many poorly constructed homes in the surrounding area require large amounts of energy to be habitable. To address this, I have focused on developing design solutions that minimise intervention and consumption. This approach, which I refer to as “Design More and Consume Less,” is inspired by the Light and Space Art Movement from the west coast of the US during the 1960’s and early 1970’s and my own curated minimalist design aesthetic that favours a limited palette.

Through my years of experience working with clients, I have learned that people often want many things and that sustainable outcomes are just one item on their list of needs and wants. With this in mind, I am committed to finding ways to use design as a force for good and to take personal responsibility for the way I design and live. I believe that many practitioners, both within and outside of architecture, share this belief that we can do more with less and that we can design more and consume less. To further explore this idea, I have been researching the work of others in related design fields to see how this premise of decoupling design and consumption can be applied in new and innovative ways.