Lin House: how to build an innovative concrete wall with bamboo

Written by

16 June 2020

•

6 min read

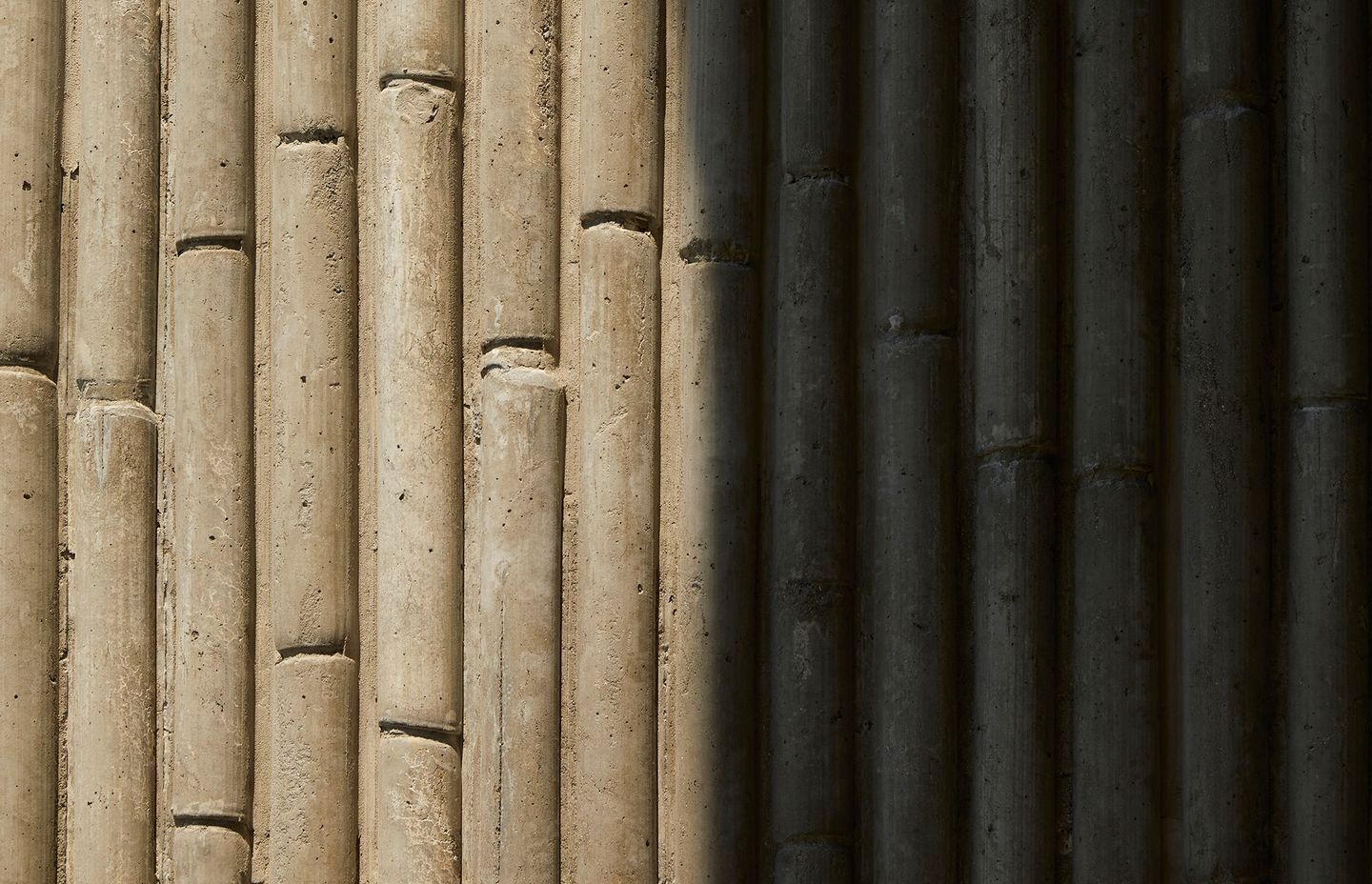

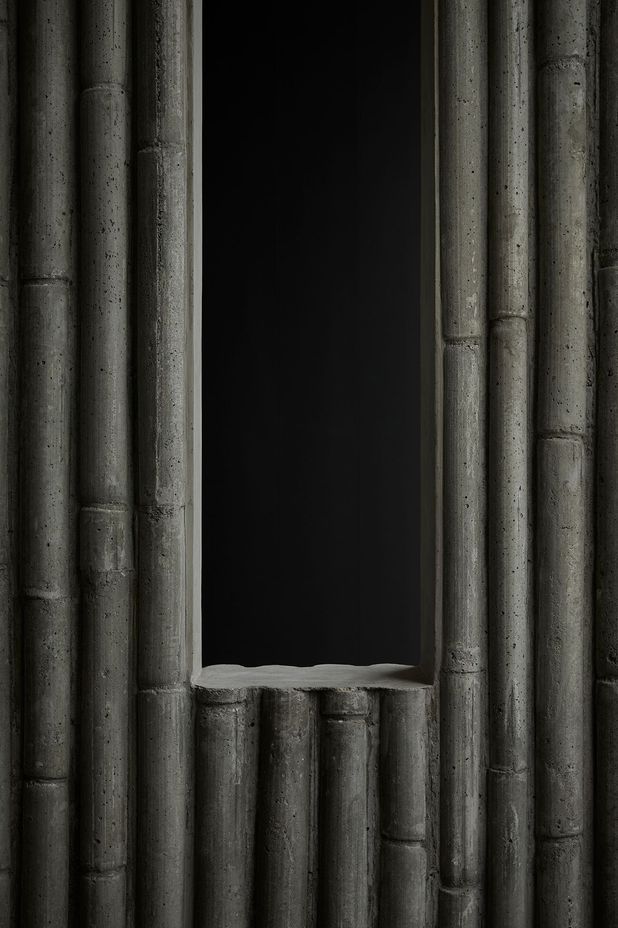

The bamboo-shuttered in-situ concrete wall at Lin House is a stunning feature of the home – has it been done before in New Zealand?

Doing the bamboo negative shuttering was something innovative and radical for us and, as far as I’m aware, it hasn’t been done before in New Zealand. Using bamboo has produced such an amazing textural element, which can be seen in the entrance foyer that leads all the way up to the balcony of the upstairs' master bedroom.

Building something original like this comes with huge risks so the results are testament to our client trusting the team to produce something so unique.

What was the rationale behind using bamboo shuttering?

It creates an architectural motif and as our clients are Asian, it was great to be able to create a reference that has meaning for them. But, building something original like this comes with huge risks so the results are testament to our client trusting the team to produce something so unique.

We made a few mock-up samples on a small 1m by 1m scale, but that is totally different than shuttering a 7m by 2m-high, double-sided feature wall that needs to hold the pressure of all that concrete on the bamboo formwork. We were very nervous about taking the formwork off!

How did you work out how to construct it?

We engaged Ross Bannan (concretologist) to assist us with the formwork design. It involved a lot of research and making prototype samples before we even started. Following several attempts at the intended design, using the outside of the bamboo as the form to create a concaved effect, we decided to try a negative form by turning the bamboo inside out; thereby, creating a replica of the actual form. We made a few mock-up samples on a small 1m by 1m scale, but that is totally different than shuttering a 7m by 2m-high, double-sided feature wall that needs to hold the pressure of all that concrete on the bamboo formwork. We were very nervous about taking the formwork off!

So you constructed the formwork yourselves?

Yes, the outer formwork that supports the concrete loads is calculated by engineers and, then, typically, we use flat timber boards to create the surface. But, here, we built it using the internal face of the bamboo with each stalk cut in half and, then the inner rings cut out to allow the concrete to flow. We had to give the bamboo just enough definition for it to look like indentations, but allow us to remove the bamboo after the concrete cures. The bamboo formwork could easily have been crushed by the pressure of the concrete, so we used expanding foam in behind and inbetween the bamboo to stop any bleeding of the concrete (the bamboo isn’t a machined straight edge and also tapers towards one end).

You obviously enjoy a challenge.

It is probably the element I’m most proud of building in my career. Our site team did a fantastic job. Dan (the architect) designed an LED strip (supplied by ECC) at each side and top/bottom of the wall and, at night, it accentuates the texture of the bamboo pattern and provides a soft light at the entrance of the house – this was really clever.

We worked collaboratively from the early stages of the project, which really helped the process because we were able to refine the structural elements and manage cost expectations.

Had you worked with Daniel Marshall Architects before Lin House?

It was my first project with Daniel Marshall Architects; although we first started working together on a project on Waiheke Island, Lin House was completed first. We worked collaboratively from the early stages of the project, which really helped the process because we were able to refine the structural elements and manage cost expectations.

All of our most successful projects have had a collaborative approach. When the client, design team and the builder all have common goals and work together it not only produces the best results, but they tend to be the most enjoyable projects for all parties. This project was no exception, Dan’s ability to deliver on his strong design principals while also working as a team to manage costs was paramount to the success of the project. He’s a real team player and I know the client is full of admiration for Dan’s team. Both Dan and I are good friends with the client – I think, when you can say that at the end of a project, it says a lot – it is important to us.

It is always our preference to be involved from an early stage in the project; it’s about balancing time, money, the aesthetic and the expectations around those elements. If you have to unwind a design later on, it can be heartbreaking for everyone, so it’s better to create a linear process and not have to back-track down the line.

How much of Lin House was constructed with in-situ concrete?

Approximately 80 per cent of the concrete structure was precast – these were the straight walls. The two elements that required to be built insitu were the bamboo wall (due to it being double sided) and the curved walls flanking the garages (due to the curved shape).

The curved in-situ walls were very difficult. For straight walls, it is easy to create a structure that deals with the forces of the concrete because you can readily hire the flat formwork, but a curved structure needs special formwork to hold the concrete in place.

The curved in-situ walls at the entrance of the garage look like they were a challenge to build too.

Yes, the curved in-situ walls were very difficult. For straight walls, it is easy to create a structure that deals with the forces of the concrete because you can readily hire the flat formwork, but a curved structure needs special formwork to hold the concrete in place. Ross designed the curved formwork for us, and we built it off-site to be craned into position. It is a bespoke design as the inner and outer formwork are obviously different radii. This system allows you to adjust the radii to suit the architectural setout. Again, we were nervous about removing the formwork, but we’re very happy with the end result.

Interview by Justine Harvey

Architectural photography by Simon Devitt.

Construction photography supplied by Lindesay Construction.