International Women's Day: balance for better

Written by

07 March 2019

•

10 min read

Friday, 8th March marks International Women’s Day 2019. In celebration of this day, ArchiPro editor Amelia Melbourne-Hayward spoke with three talented women architects at different stages in their careers about some of their experiences while working in architecture in New Zealand.

NATASHA MARKHAM

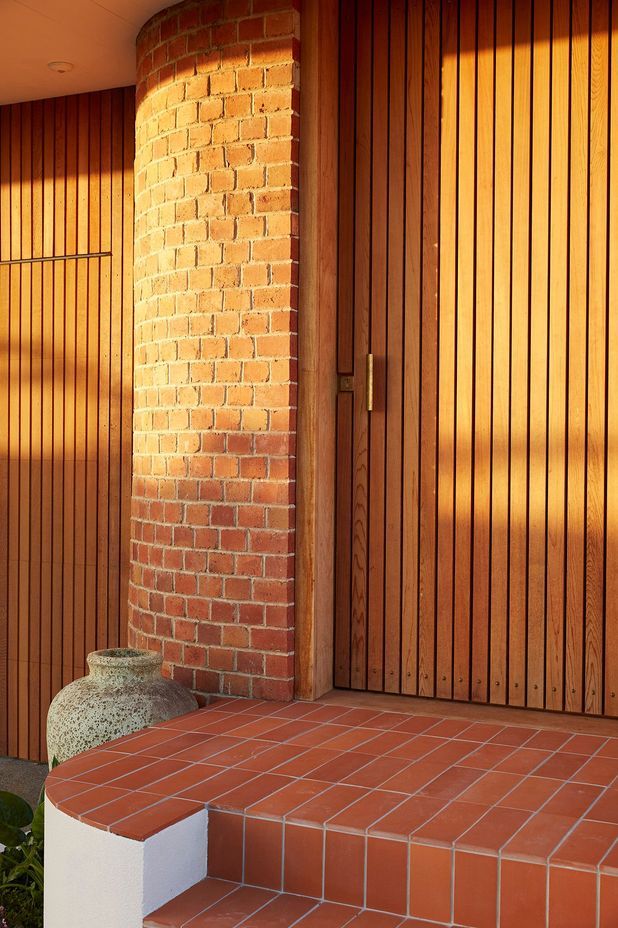

Natasha Markham is a registered architect and urban designer. She is the director of Auckland practice MAUD (Markham Architecture + Urban Design) and she also co-hosts architectural podcast 76 Small Rooms. The image above is MAUD's Eden Terrace House project in Auckland.

You started your practice MAUD when your children were young. Do you feel this gave you more flexibility and balance than if you were working for someone else?

Flexibility was a factor in deciding to set up my own practice and being my own boss allowed me a degree of oversight and influence in the way projects played out. I’m quite a good planner so, while you can’t account for every scenario, having the ability to chart a course and manage expectations helped with the juggling of parenting and practice.

Work practices are changing slowly but it really suited me to be able to have just one or two residential or smaller commercial projects on the go when the boys were very young, and to grow that organically as my time freed up.

How do you think larger firms can support women to continue their career, while also managing the challenges of motherhood?

It’s more about how practices can support parents in general or, in fact, anybody in a caregiver situation as, increasingly, people have older parents who might become sick. It comes back to the dialogue between management and employees about their career ambitions and their long-term progression. I’ve heard a few blanket statements like, "The women in our practice are not interested in leadership positions." I wonder if the right questions are being asked, as a lot of it is about timing.

All practices should be interested in understanding what their staff members’ motivations and goals are, and keeping a check on how they’re evolving. People really are your best resource and businesses with diverse teams get better results.

Do you think women architects are more reticent to promote their work in the public arena?

It’s a hard one to answer, as I’m not sure if we see less work by women architects because they are shy to promote themselves, or if there are fewer women in the industry and fewer in leadership positions, so, perhaps, they’re not in a place where they can advocate for their work. It could be a mix of those reasons, too.

Any moves to normalise the idea that women create architecture are really helpful. Architecture+Women•NZ has been doing a fantastic job to increase the visibility of women in the profession and to promote their work. The New Zealand Institute of Architects (NZIA) has also sourced a stellar line-up of female speakers for every recent in:situ conference and, against any measure, those women are producing fantastic work.

LINDLEY NAISMITH

Lindley Naismith is a director at Auckland-based practice Scarlet Architects, which established the female-only Scarlet Prize in Architecture in 2018. She is a founding member of Architecture+Women•NZ and immediate past chair of the NZIA Auckland branch.

You formed Scarlet Architects with co-director Jane Aimer around 11 years ago. Having two women at the helm of an architectural practice is quite unusual, both then and now. How did this come about?

It was a big decision to join forces, because having your own firm is very different to working for someone. Jane and I were friends at university and had been working out of the same premises, running separate practices, when we combined forces, so it was more about timing than a conscious decision to create a female-led practice. In Jane’s case, she had three children, so she wanted to create a professional life that fitted with family commitments.

We are at the helm of Scarlet Architects because we are determined and committed to the profession and have both derived a great deal of personal satisfaction from working in architecture; that’s probably no different to anybody who’s been there as long as we have.

There must have been some challenges along the way…

As most of the people in the building industry are still men, it’s definitely a male-dominated environment, with the attitudes and behaviours that go with that. There was a joke around when I was young that went: "Don’t worry if the men you’re working with seem critical of you as a woman architect – they all think that architects are women anyway!"

It’s not as hard if your practice is based around residential work, as Scarlet’s is, as there is a perception that women understand the domestic world better than men and that women are ‘good at designing kitchens’.

And, in those days anyway, the scale of the residential work was more manageable for a smaller practice. Mike Dowsett is one of our directors and he is male, so we have gender balance in our leaders and the practice is also nearly half female and half male.

What are some changes you've seen through the years regarding women in architecture in New Zealand?

I’d say there hasn’t been much change until recently. Architecture+Women•NZ’s agenda of increasing the visibility of women in architecture has made a huge difference and we now have a heightened interest and awareness, which has seen much more hard information coming through.

For many years now, the numbers of men and women graduating from architecture school have been roughly equal – lately, even slightly more women than men but, when it came to registration, the proportion of women dropped to 30 per cent. The most recent statistic from The New Zealand Architects' Registration Board (NZRAB) is that there’s been a big leap in the proportion of women registering – it’s now 40 per cent, which is very encouraging.

What is one piece of advice you'd give to any young woman thinking of a career in architecture today?

Be determined and committed and, additionally, consider what your aspirations are for a family. The architectural profession is not as highly paid or valued by society as other professions so, if you have a partner and are thinking about having a family, it pays to bear in mind that it’s generally the architect in the relationship who tends to come under pressure to be the stay-at-home parent.

Many women possess the ability and energy to have a career and raise children at the same time, but the extraordinary effort and high level of support required needs to be understood and managed, both within the family and the workplace.

RAUKURA TUREI

A registered architect currently working for Monk Mackenzie in central Auckland, Raukura Turei, of Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki and Ngā Rauru iwi, is also an actress who has appeared in local films and an artist whose most recent work is being exhibited at the Tokyo Art Fair in Japan.

With more women studying architecture today than ever before, do you think that architecture's stereotype of being a 'white male’s club' is changing?

It’s about bloody time really! The reality is that over half of architecture students graduating are women and I find that there are many women working in architecture, they’re just often less visible.

When I started at Stevens Lawson Architects (SLA) after graduating from the University of Auckland in 2011, women accounted for 50 per cent of the office, a statistic I see in many firms. My mentor, Lynda Simmons, and the project lead at SLA, Yvette Overdyck, are talented female architects so I’ve never felt that my ambition and ideas in the world of architecture weren’t attainable as a woman.

Now I am working in a more commercial environment so the notion of the 'welcome to the boy's club' is becoming more apparent. As project architect on a large commercial project, it's not surprising that 90 per cent of my team are male. I’m finding the developer-driven realm of architecture very much male dominated, whereas, when I’ve worked on civic, community or public projects – such as theatres or schools – the project and consultant teams have been more diverse. All the peripheral industries that comprise an architecture project have some catching up to do.

As a young women architect, do you feel that you have been given the same opportunities as your male peers?

All the opportunities that I have had so far, I have worked really hard for and not been shy to front foot – with the support of my whanau and through scholarships, architecture networks and institutions. That trajectory comes back to my upbringing by a strong, determined mother who instilled in me the importance of education and working hard. I had strong female mentors and whanau around me growing up and through university, so I never had the sense that women couldn’t do anything.

The greater issue I see now in the industry is not one of gender equality but access and privilege. If we are supported and have the financial backing, we can all achieve what we are driven towards. This is not the case for so many of our rangatahi.

The obvious crunch point for equality surrounds women who decide to have children, who are often faced with the inevitable setback of having to leave the workforce to be a mother – something I am yet to face. This shouldn't be seen as a handicap and can by all means be embraced in a positive light. Women are multi-taskers and we juggle so much more than just our jobs. It requires a culture of support, awareness and empathy around the idea that, yes, women can do anything, but not all at the same time. The expectation that we have to do everything at once to prove we’re as worthy as our male colleagues is a harmful ethos for women.

What do you see as the future of the architecture industry in New Zealand?

I’d like to see the people involved in the making of place, our urban landscape and communities in our industry to reflect the faces of the people that they’re serving. While half of those are women, there are also more people marginalised by poverty, access to education and systemic racism in this country. This is most evident in our Tangata Whenua and Pacific communities.

The future is those who are working with our rangatahi and our youth, and those in positions of privilege who use their voice for those who cannot. In terms of a single vein of thinking, the idea of the ‘white male’s club’ no longer serves New Zealand. Nor does unconsidered and cheaply-built suburbia sprawling into our countryside, for that matter.